The case

“Hello Easypromos. I know how to win all your Facebook voting contests. What will you give me if I tell you how?” The user signed his email with a false name which didn’t correspond to any user who’d registered with Easypromos or participated in a contest. My colleagues in the technical development department took this email as a challenge and began investigating the case.

The first thing they did was to analyze the email – in particular the headers, which included information regarding the IP address the message was sent from. This IP address was contrasted with the IP addresses of all users who’d participated in contests via the Easypromos platform. One participant was located: he was from Portugal and he’d won a photo contest by obtaining the most votes for his entry.

In order to participate in that photo contest all participants had had to register using their Facebook account. This made it possible for us to locate and analyze the public profile of this Facebook user. The profile was limited, owing to the user’s privacy settings. However, some shared posts, mostly about surfing, were visible on the user’s Timeline. Interestingly, the majority had been shared from a single website.

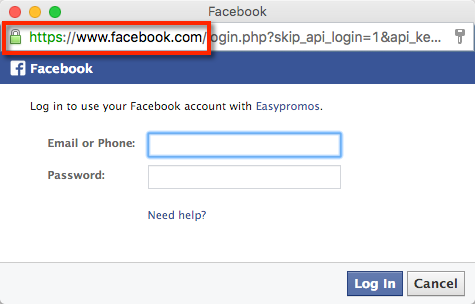

In order to streamline registration, participants were given the option of connecting their Facebook account via the standard Facebook login system, used for registration by many websites

My colleagues then turned the focus of their investigation to the website. First they analyzed unrestricted public information, such as the website’s domain name. The technical and administrative contact details of the domain name coincided with the name of the user in Facebook: the user was also the owner of the website.

It appeared to be website about surfing, containing travel tips, users’ experiences, opinions regarding equipment, and so on. It also included a forum, in which users asked and answered questions. In order to participate in the forum users had to register, and they were given the opportunity to do so using their Facebook account via the standard Facebook Login system commonly used by many websites with registration. Users who registered using their Facebook account were identified with their Facebook name and profile photo.

Our breakthrough came when my colleagues took one of the Facebook profiles listed in the forum and compared it with the list of users who voted for the winning entry in the photo contest. We found him: the forum member had indeed been one of the voters. We picked another forum member and made the same comparison. One more, we discovered that the user had voted for the winning photo. We found the same pattern again and again. In fact, almost 100% of forum members had seemingly voted for the photo contest winner.

Of course, it was possible that the user had merely used the forum, or sent its members a newsletter, to request that they vote for his photo. But then why did he write to us to say he’d found a way of winning all our contests? Using a forum to ask members for votes might work from time to time, but it wouldn’t be possible to this for every contest. Forum members would soon get fed up of being used in such a way. We decided to analyze the public profiles of those who’d voted in the contest. We found that their profiles did not fit with the profiles of users who normally participate in our contests, and, furthermore, looking through their Timelines we couldn’t find any instance of the winning photo being shared by these users.

We wrote to 20 users. 12 responded: none had ever voted for this participant.

The next step was to get in touch with these users to ask them directly via private Facebook messaging whether or not they’d really voted for the winning photo. We identified ourselves using our personal Facebook profiles, making it clear that we formed part of the Easypromos team, and asked them directly whether or not they’d voted for the photo. We wrote to 20 users. 12 responded, all saying that they’d never voted for the winning participant.

Our suspicions had been confirmed: this individual had used the profiles of members of his forum to vote for his own entry. He was using their email addresses and passwords to log into their Facebook accounts and cast a vote in their names. How did he get their passwords? Well, many of them registered for his forum with the same password they used to access their Facebook accounts.

We investigated further and discovered online tutorials, videos and documents giving ideas and techniques for stealing users’ access data. In addition to the method that we’ve outlined above, another common technique is Facebook Phishing. This involves displaying a false login page which seems identical to the authentic Facebook login page. The victims, believing they’re connected to Facebook, enter their email addresses and passwords in an attempt to log into their accounts. However, in reality users are supplying their login details to the phisher behind the false webpage.

Our four tips

How can you avoid having your Facebook access details stolen? Here are four tips:

Change your Facebook password frequently

It’s a good idea to change your Facebook password every 90 days for security reasons.

If you use your Facebook account to register for a website – which then asks you to provide an additional password – don’t use the same password as you use for Facebook

Facebook enables websites to give users the chance to sign up and log in quickly and securely, so that an additional password is not normally required. However, some websites might also request an extra password to complete the registration process. If this happens to you, make sure the additional password is not the same as your Facebook password.

Always verify the URL and SSL certificate when connecting to Facebook

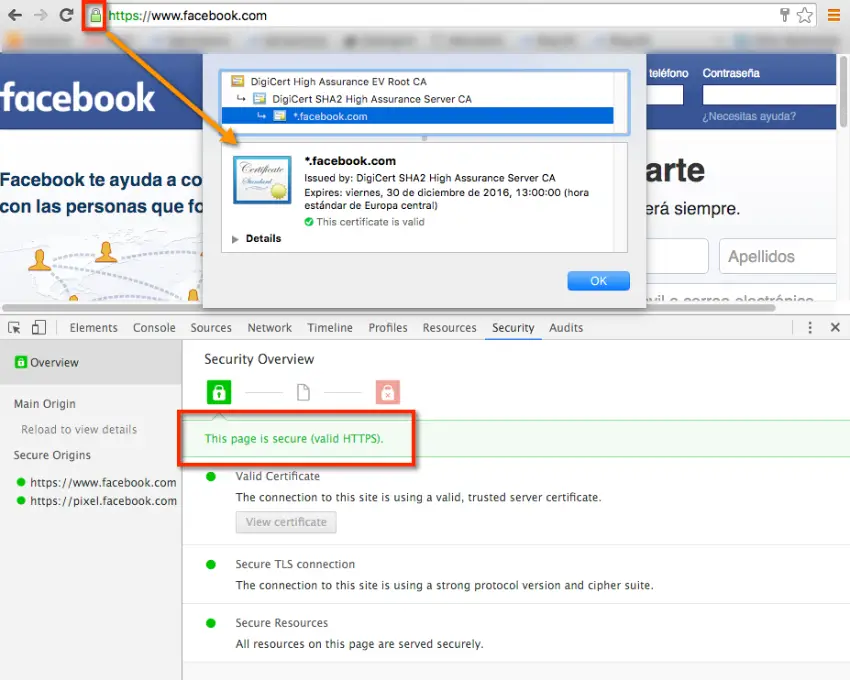

Facebook phishing is when users are deceived into trusting a fake version of the Facebook Login Page. This situation may arise when a user accesses the Facebook Login Page from an external link. When accessing Facebook from an external link we suggest you carry out the following checks to ensure you’re not the victim of a phishing attack:

- Verify that the URL is a domain name and not an IP address. E.g. http://123.214.56.72

- Check that the domain name is Facebook: facebook.com and not a subtly altered version, such as www.faceebook.com or www.faceboook.com

- Verify that the access protocol is HTTPS: https://www.facebook.com. If in doubt, click on the padlock for a certificate of validity

Verify the validity of the application which is requesting additional permissions to access your Facebook account

Many websites and applications offer users the chance to connect via their Facebook Page, thus streamlining the signup process and taking advantage of additional features provided by Facebook, such as sharing, displaying friends, etc. In order to carry out these actions the user will need to authorize Facebook permissions. This is another situation in which users might find themselves subject to an attack. To prevent this from happening, make sure that:

- The permissions pop-up is from an official Facebook URL.

- The permissions pop-up opens with HTTPS protocol. Verify the security certificate if you’re in doubt.

- The application contains a link to the privacy policy and conditions of use.

Finally, we recommend you read the following article, in which Facebook provides a complete list of tips for protecting your Facebook account from unauthorized access and theft.